Chapter 88: Static Libraries: Linking, Code Duplication, & Disadvantages

Chapter Objectives

Welcome to this chapter on static libraries. By the end of this section, you will have a thorough understanding of this fundamental concept in systems programming. You will be able to:

- Understand the role of the linker and the process of static linking within the C/C++ compilation pipeline.

- Implement a custom static library from source code, including compiling object files and using the

ararchiver tool. - Configure a build process to correctly link an application against a custom static library, managing header files and linker flags.

- Analyze the structure of executables and the impact of static linking, specifically identifying code duplication and its disadvantages in terms of memory and storage.

- Debug common linking errors, such as “undefined reference” issues, by troubleshooting library paths, names, and command-line order.

Introduction

In the world of software development, we rarely build applications from a completely blank slate. Instead, we stand on the shoulders of giants, leveraging pre-written, pre-tested code to perform common tasks. This principle of code reuse is the bedrock of modern programming, allowing us to focus on the unique logic of our application rather than reinventing the wheel for tasks like printing to the console, performing mathematical calculations, or managing network connections. Libraries are the primary mechanism for sharing and reusing this code.

This chapter delves into one of the two major types of libraries in the Linux world: the static library. Historically, static libraries were the original method for sharing code, providing a simple and robust way to bundle reusable functions into a single, convenient package. In the context of embedded Linux, the concept of static linking has a nuanced role. For very simple, single-purpose devices where predictability and self-containment are paramount, a statically linked executable can be advantageous. It has no external dependencies, making deployment a simple matter of copying a single file to the target system.

However, this simplicity comes at a significant cost, primarily in the form of code duplication. As we will explore, the static linking process copies code directly into every application that uses it. In a resource-constrained embedded system, where flash storage and RAM are precious commodities, this duplication can be prohibitively expensive. Understanding how static libraries work, why they lead to this duplication, and what their trade-offs are is therefore not just an academic exercise; it is a critical piece of knowledge for any embedded systems developer aiming to build efficient, maintainable, and optimized systems. In this chapter, we will build our own static library, link it to a program on our Raspberry Pi 5, and dissect the results to understand its profound implications.

Technical Background

To fully appreciate the function and drawbacks of static libraries, we must first place them within the broader context of how a program is created. The journey from human-readable source code to a machine-executable file is a multi-stage process, often referred to as the compilation pipeline. The final and perhaps most crucial stage of this pipeline is linking, and it is here that libraries play their part.

The Compilation and Linking Pipeline

When you invoke the GNU Compiler Collection (gcc) to compile a simple C program, it orchestrates a four-step sequence. First, the preprocessor (cpp) scans the source code, handling directives like #include by pasting in the contents of header files and expanding #define macros. The resulting, expanded source code is then passed to the compiler proper, which parses the C code and translates it into the assembly language specific to the target architecture (like ARMv8 for the Raspberry Pi 5). Third, the assembler (as) takes this assembly code and converts it into machine-readable binary instructions, producing an object file (e.g., main.o).

graph TD

subgraph "Inputs"

direction LR

A[/"Source Code<br><i>(main.c)</i>"/]

H[/"Header Files<br><i>(e.g., stdio.h)</i>"/]

end

subgraph "Compilation Pipeline"

direction TB

P("<b>1. Preprocessor</b><br>(cpp)")

C("<b>2. Compiler</b><br>(cc1)")

AS("<b>3. Assembler</b><br>(as)")

O[("Object File<br><i>main.o</i>")]

L("<b>4. Linker</b><br>(ld)")

end

subgraph "Library Inputs"

direction LR

SL[/"Static Library<br><i>(e.g., libc.a)</i>"/]

end

subgraph "Output"

direction LR

E[/"Executable File<br><i>(my_program)</i>"/]

end

A --> P

H --> P

P --> C

C --> AS

AS --> O

O --> L

SL --> L

L --> E

classDef primary fill:#1e3a8a,stroke:#1e3a8a,stroke-width:2px,color:#ffffff

classDef endNode fill:#10b981,stroke:#10b981,stroke-width:2px,color:#ffffff

classDef process fill:#0d9488,stroke:#0d9488,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

classDef system fill:#8b5cf6,stroke:#8b5cf6,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

class A,H primary

class P,C,AS,L process

class SL system

class E endNode

This object file, however, is not yet a complete, runnable program. It contains the machine code for the functions defined in its corresponding source file, but it also contains placeholders. For instance, if your code calls a function like printf, the object file contains a reference—a “symbol”—named printf, but it does not contain the actual code for printf. It merely holds a promise that the code for printf will be made available later. This is where the final step, linking, comes in. The linker (ld) is the tool responsible for stitching together one or more object files into a single, executable file. Its two primary responsibilities are symbol resolution and relocation. Symbol resolution is the process of finding the missing pieces—locating the machine code for every referenced symbol (like printf) and ensuring that every function call has a corresponding definition. Relocation involves adjusting the memory addresses in the object files so they can be correctly placed within the final executable’s memory map.

What is a Static Library?

A static library is, in its simplest form, an archive of object files. It is a single file (conventionally ending with a .a extension, for “archive”) that bundles together many individual .o files for convenience. The tool used to create and manage these archives is ar. A static library is not fundamentally different from a .zip or .tar file; it is a container. For example, the standard C library can be provided as libc.a, which contains the object files for printf.o, scanf.o, strlen.o, and hundreds of other standard functions.

By grouping these related object files into a single archive, the library provides a clean way to distribute a collection of functions. When you want to use a function from the library, you don’t need to know which specific object file it resides in. You simply tell the linker to look inside the library’s archive, and the linker takes on the responsibility of finding the correct object file and extracting its contents.

The Static Linking Process in Detail

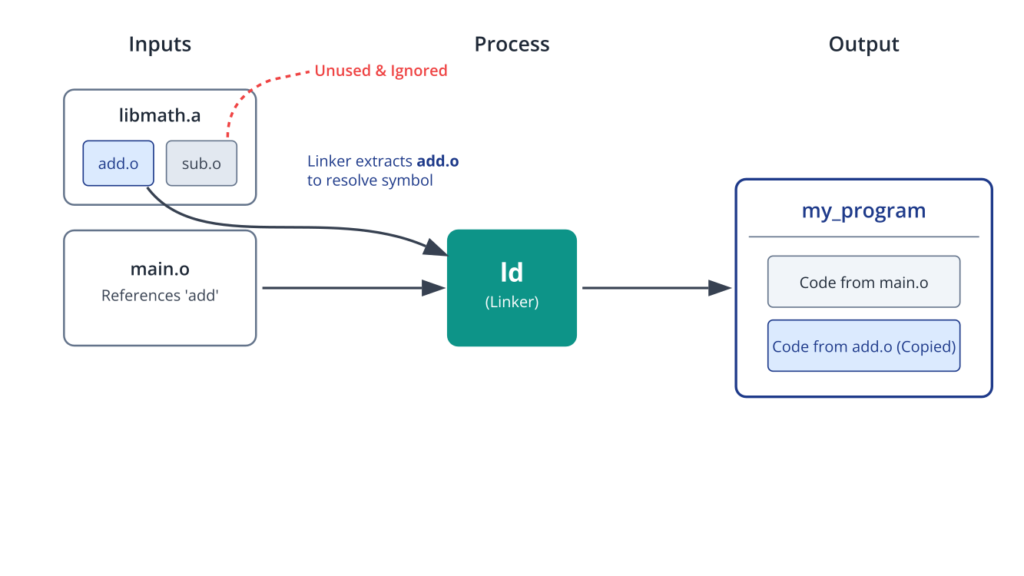

The magic of static linking happens when you instruct the linker to use a static library to resolve symbols. Let’s imagine you have written a program in main.c that calls a function add(int, int). You also have a static library, libmath.a, which contains the object files add.o and sub.o.

When you compile and link your program with a command like gcc -o my_program main.c -L. -lmath, you are telling the linker to consider the libmath.a archive as a source for resolving any symbols that are not defined in main.c. The linker begins by processing main.o. It builds a list of symbols that main.o defines and a list of symbols that it references but does not define. In this list of “undefined references” will be the symbol add.

Now, the linker turns its attention to libmath.a. It scans the index of the archive (a table of contents, essentially) to see which object files within the archive define the symbols it’s looking for. It finds that add.o contains the definition for the add symbol. At this point, the linker behaves as if you had included add.o on the command line directly. It extracts the entire contents of add.o—all of its code and data—and copies it directly into the final executable file, my_program.

Crucially, the linker only pulls in the object files it needs. In our example, since main.c never called any function from sub.o, the linker completely ignores sub.o. It remains in the libmath.a archive but its code is not copied into my_program. This selective inclusion is a key feature, preventing executables from being bloated with unused library code.

After this process is complete, the my_program executable is a self-contained, monolithic file. It contains your program’s machine code from main.o as well as a full copy of the machine code from add.o. It has no further need for libmath.a; the library could be deleted from the system, and my_program would still run perfectly because the necessary code has been fully integrated into it.

The Perils of Code Duplication

The self-contained nature of statically linked executables seems like a major advantage, and in some isolated cases, it can be. However, in any system with more than a handful of programs, it becomes a significant liability. This leads us to the primary disadvantage of static linking: massive code duplication.

Consider a realistic scenario on your Raspberry Pi. Imagine you have ten different applications (app1, app2, …, app10) that all need to perform logging. You wisely create a liblog.a static library with helpful logging functions. Each of these ten applications is then statically linked against liblog.a. The result is that ten separate copies of the logging functions’ machine code are embedded across the ten executables. If liblog.a is 200 KB, you have just consumed 2 MB of disk space for what is functionally the same code.

This problem extends from disk storage into active memory (RAM). When you run app1 and app2 simultaneously, the operating system’s loader will load both executables into RAM. Because the library code is part of each executable, two copies of the liblog functions will be present in physical memory. Scale this up to ten applications, and you are wasting a significant amount of a precious embedded resource.

graph TD

A["liblog.a<br/>(200 KB)<br/>Source Library"]

A -->|"Statically Linked Into"| B1

A -->|"Statically Linked Into"| C1

A -->|"Statically Linked Into"| D1

subgraph SG1 ["app1"]

B1["App Code"]

B2["Copy of<br/>liblog code"]

end

subgraph SG2 ["app2"]

C1["App Code"]

C2["Copy of<br/>liblog code"]

end

subgraph SG3 ["app3"]

D1["App Code"]

D2["Copy of<br/>liblog code"]

end

B2 --> E["Result: Wasted Disk Space & RAM<br/>3 copies of the same library code exist on the system"]

C2 --> E

D2 --> E

style A fill:#e6fffa,stroke:#0d9488,stroke-width:2px

style B1 fill:#f1f5f9,stroke:#64748b,stroke-width:1px

style B2 fill:#e9d5ff,stroke:#8b5cf6,stroke-width:1px

style C1 fill:#f1f5f9,stroke:#64748b,stroke-width:1px

style C2 fill:#e9d5ff,stroke:#8b5cf6,stroke-width:1px

style D1 fill:#f1f5f9,stroke:#64748b,stroke-width:1px

style D2 fill:#e9d5ff,stroke:#8b5cf6,stroke-width:1px

style E fill:#fef2f2,stroke:#ef4444,stroke-width:2px

style SG1 fill:#ffffff,stroke:#64748b,stroke-width:2px

style SG2 fill:#ffffff,stroke:#64748b,stroke-width:2px

style SG3 fill:#ffffff,stroke:#64748b,stroke-width:2pxThe Maintenance and Security Nightmare

The duplication problem creates a secondary, equally severe issue: maintenance. Imagine a critical security vulnerability is discovered in your liblog.a library. To patch the system, you must now find every single application that was statically linked against the old library, re-link it with the new, patched version of liblog.a, and redeploy the updated executable.

This is a brittle and error-prone process. If you miss even one application, it remains a vulnerable entry point on your system. There is no central point of update. You cannot simply replace the liblog.a file on the filesystem and have the fix propagate; the old, vulnerable code is permanently embedded in the executables until they are rebuilt. This stands in stark contrast to dynamic linking (which you will learn about in the next chapter), where a single update to a shared library file on disk can patch all applications that use it simultaneously. For this reason, modern desktop and server Linux distributions, as well as complex embedded systems, heavily favor dynamic linking. Static linking is generally reserved for specific use cases, such as building tools for a recovery environment where you cannot rely on the main system’s libraries being present or intact.

graph TD

subgraph "The Maintenance Nightmare"

direction TB

A("<b>Vulnerability Found</b><br>in liblog.a") --> B{{"For EACH application..."}}

B --> P1("Find app1") --> L1("Re-link app1 w/ patched liblog.a") --> D1("Re-deploy app1")

B --> P2("Find app2") --> L2("Re-link app2 w/ patched liblog.a") --> D2("Re-deploy app2")

B --> P3("Find appN") --> L3("Re-link appN w/ patched liblog.a") --> D3("Re-deploy appN")

subgraph "Verification"

C{"Did you find ALL applications?"}

C -- "No, missed one" --> V[("System Remains Vulnerable!")]

C -- "Yes, all found" --> S[("System Patched")]

end

D1 --> C

D2 --> C

D3 --> C

end

classDef primary fill:#1e3a8a,stroke:#1e3a8a,stroke-width:2px,color:#ffffff

classDef endNode fill:#10b981,stroke:#10b981,stroke-width:2px,color:#ffffff

classDef decision fill:#f59e0b,stroke:#f59e0b,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

classDef process fill:#0d9488,stroke:#0d9488,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

classDef check fill:#ef4444,stroke:#ef4444,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

classDef warn fill:#eab308,stroke:#eab308,stroke-width:1px,color:#1f2937

class A check

class B,C decision

class P1,L1,D1,P2,L2,D2,P3,L3,D3 process

class V warn

class S endNode

Practical Examples

Theory is essential, but there is no substitute for hands-on practice. In this section, we will walk through the complete process of creating, linking, and analyzing a static library on your Raspberry Pi 5. We will create a small math library, use it in an application, and witness the effects of static linking firsthand.

Project Setup and File Structure

First, let’s organize our project. Open a terminal on your Raspberry Pi and create the following directory structure. This organization cleanly separates the library source, the application source, and the final build artifacts.

mkdir -p static_linking_demo/lib static_linking_demo/src

cd static_linking_demo

Our file structure will look like this:

static_linking_demo/

├── lib/

│ ├── my_math.h

│ ├── add.c

│ └── sub.c

└── src/

└── main.c

Step 1: Creating the Library Source Code

We will create a simple library with two functions: one for addition and one for subtraction.

1. The Header File (lib/my_math.h)

This public header file contains the function prototypes. Any application wanting to use our library will need to include this file.

// lib/my_math.h

// This is the public interface for our math library.

// It declares the functions that are available for other programs to use.

#ifndef MY_MATH_H

#define MY_MATH_H

/**

* @brief Adds two integers.

* @param a The first integer.

* @param b The second integer.

* @return The sum of a and b.

*/

int add(int a, int b);

/**

* @brief Subtracts the second integer from the first.

* @param a The first integer.

* @param b The second integer.

* @return The result of a - b.

*/

int subtract(int a, int b);

#endif // MY_MATH_H

2. The Implementation Files (lib/add.c and lib/sub.c)

These files contain the actual code for our functions.

// lib/add.c

// Implementation of the add function.

#include "my_math.h"

int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

// lib/sub.c

// Implementation of the subtract function.

#include "my_math.h"

int subtract(int a, int b) {

return a - b;

}

Step 2: Compiling and Archiving the Library

Now that we have the source code, we need to compile it into object files and then package those object files into a static library archive.

1. Compile to Object Files

We use gcc with the -c flag, which tells the compiler to stop after the assembly stage and produce an object file (.o) instead of a full executable. We’ll also use -Ilib to tell the compiler to look in the lib directory for header files.

# Navigate to the project root if you aren't there

# Compile add.c into add.o

gcc -c lib/add.c -Ilib -o add.o

# Compile sub.c into sub.o

gcc -c lib/sub.c -Ilib -o sub.o

After running these commands, you will have add.o and sub.o in your project’s root directory.

2. Create the Static Library Archive

Next, we use the ar tool to create the archive, which we will name libmy_math.a. The name is important: linkers look for files named lib<name>.a, which corresponds to the -l<name> flag.

# Create the archive and add the object files

# r: insert the files into the archive, replacing any existing ones

# c: create the archive if it doesn't exist

# s: write an object-file index into the archive (same as running ranlib)

ar rcs libmy_math.a add.o sub.o

Tip: The

sflag foraris a modern convenience that runs the equivalent of theranlibcommand.ranlibgenerates an index of symbols inside the archive, which helps the linker find object files more quickly. On older systems, you had to runranlib libmy_math.aas a separate step.

You now have a static library, libmy_math.a, ready to be used. You can inspect its contents with ar -t:

$ ar -t libmy_math.a

add.o

sub.o

Step 3: Creating and Linking the Main Application

Let’s write a simple program that uses our new library.

1. The Application Source Code (src/main.c)

// src/main.c

// A simple program to demonstrate using our static library.

#include <stdio.h>

#include "my_math.h" // Include our library's header

int main() {

int x = 10;

int y = 5;

int sum = add(x, y);

int difference = subtract(x, y);

printf("Welcome to the Static Library Demo!\n");

printf("The sum of %d and %d is %d\n", x, y, sum);

printf("The difference between %d and %d is %d\n", x, y, difference);

return 0;

}

2. Compile and Link the Application

This is the final, crucial step. We compile main.c and tell gcc to link it with our library.

# Compile main.c to an object file first

gcc -c src/main.c -Ilib -o main.o

# Now, link main.o with our library to create the final executable

gcc -o my_program main.o -L. -lmy_math

Let’s break down that final gcc command:

-o my_program: Specifies the name of the output executable file.main.o: The main object file for our application.-L.: This tells the linker to look for library files in an additional directory. The.means “the current directory.” Without this, the linker would only search standard system paths like/usr/lib.-lmy_math: This is the key flag. It tells the linker to find and link with the library namedmy_math. The linker automatically prependsliband appends.ato the name, so it searches forlibmy_math.a.

Warning: The order of arguments matters! The linker processes files from left to right. You must place the library (

-lmy_math) after the object file (main.o) that uses it. If you reverse them, the linker will not yet know about the “undefined reference” toaddwhen it sees the library, and the link will fail.

Run your program to see the result:

$ ./my_program

Welcome to the Static Library Demo!

The sum of 10 and 5 is 15

The difference between 10 and 5 is 5

Step 4: Analyzing the Result and Proving Duplication

We have a working program, but how can we prove that the library code was copied into it?

1. Check File Sizes

First, let’s look at the sizes of the files involved.

$ ls -lh my_program libmy_math.a

-rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 2.5K Aug 1 12:11 libmy_math.a

-rwxr-xr-x 1 pi pi 16K Aug 1 12:11 my_program

The executable my_program is 16 KB. It contains not only our code but also standard C startup code and code for printf, all linked statically by default for simple programs.

2. Inspect the Symbol Table

The nm utility can list the symbols in an object file or executable. Let’s look for our functions. A T in the output indicates the symbol is in the text (code) section.

$ nm my_program | grep -E 'add|subtract'

00000000000106f0 T add

0000000000010704 T subtract

This is definitive proof. The symbols add and subtract are present in the executable’s symbol table, marked as defined functions within its own code section. The code was copied.

3. Demonstrate Duplication

Now, let’s create a second, almost identical program.

// src/main2.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include "my_math.h"

int main() {

printf("Program 2 calling add: %d\n", add(100, 200));

return 0;

}

Compile and link this second program:

gcc -c src/main2.c -Ilib -o main2.o

gcc -o my_program2 main2.o -L. -lmy_math

Now, check the file sizes again:

$ ls -lh my_program my_program2 libmy_math.a

-rw-r--r-- 1 pi pi 2.5K Aug 1 12:11 libmy_math.a

-rwxr-xr-x 1 pi pi 16K Aug 1 12:11 my_program

-rwxr-xr-x 1 pi pi 16K Aug 1 12:11 my_program2

Both my_program and my_program2 are 16 KB. The total disk space used by just these two small programs is 32 KB. Both contain their own private copy of the code from libmy_math.a. This is the cost of static linking in action. In a large system with hundreds of executables sharing dozens of libraries, this wasted space would quickly grow from kilobytes to megabytes, or even gigabytes.

Common Mistakes & Troubleshooting

When working with static libraries, several common issues can trip up even experienced developers. Understanding these pitfalls will help you debug linking problems quickly.

Exercises

Apply your knowledge with these hands-on exercises.

- Create a String Utilities Library.

- Objective: Build and use a new static library from scratch.

- Steps:

- Create a new library named

libstrutil.a. - Implement two functions in separate

.cfiles:to_uppercase(char *str)andto_lowercase(char *str). These functions should modify the string in-place. - Create a corresponding header file,

strutil.h. - Write a main program that uses this library to convert a string to all uppercase, print it, then convert it to all lowercase and print it again.

- Create a new library named

- Verification: The program should compile without errors and produce the correctly modified strings as output.

- Updating an Existing Library.

- Objective: Practice the workflow for modifying and updating a library.

- Steps:

- Add two new functions,

multiply(int, int)anddivide(int, int), to themy_mathlibrary from the chapter example. - Compile the new source files to object files.

- Use the

arcommand to add the new object files to the existinglibmy_math.aarchive without recreating it from scratch. (Hint: check thearman page). - Modify

main.cto call the newmultiplyanddividefunctions. - Re-link the application (you do not need to recompile

main.c, only re-linkmain.o).

- Add two new functions,

- Verification: The program should link successfully and print the correct results for all four math operations.

- Analyzing Code Duplication.

- Objective: Quantify the disk space overhead of static linking.

- Steps:

- In the chapter example, you already have

my_programandmy_program2. - Use the

sizecommand onmy_program,my_program2, andlibmy_math.a. Thesizecommand gives a more detailed breakdown of the text, data, and bss segments. - Calculate the total size of

my_program+my_program2. - Compare this total to the size of

libmy_math.a. - Write a short text file (

analysis.txt) explaining your findings. How much larger is the combined size of the executables compared to the library they both use? What does this imply for a system with 100 such programs?

- In the chapter example, you already have

- Verification: Your

analysis.txtfile should contain clear calculations and a logical conclusion about the cost of code duplication.

- Dissecting an Archive.

- Objective: Become proficient with the

arutility for managing archives. - Steps:

- Using the

libmy_math.aarchive, perform the following operations. - Delete just the

sub.omember from the archive. Verify withar -tthat it is gone. - Try to re-link

my_program(which usessubtract). Observe the “undefined reference” error. - Add

sub.oback into the archive. - Re-link

my_programagain and verify that it now succeeds.

- Using the

- Verification: Successful completion of the command sequence and observation of the expected linker behavior at each step.

- Objective: Become proficient with the

Summary

This chapter provided a deep dive into the concept of static libraries and their role in the software development lifecycle. We have moved from theory to practice, solidifying your understanding of this fundamental building block.

- Static Libraries are Archives: A static library (

.afile) is simply an archive of pre-compiled object (.o) files, created with thearutility. - Linking Copies Code: The static linking process resolves undefined symbols by finding the required object file within the library and copying its entire contents directly into the final executable.

- Executables are Self-Contained: A statically linked program has no external library dependencies at runtime, making it portable and predictable.

- The High Cost of Duplication: The primary disadvantage of static linking is code duplication. Every application that uses a static library gets its own private copy, wasting significant disk space and RAM.

- Maintenance is Difficult: Bug fixes or updates to a static library require every application that uses it to be manually re-linked and redeployed.

- Linker Flags are Key: Proper use of the

-L(library path) and-l(library name) flags, along with correct command-line order, is essential for successful linking.

With this knowledge, you are now equipped to make informed decisions about when—and when not—to use static linking in your embedded Linux projects. You also have the foundational knowledge required to appreciate the problem that our next topic, dynamic linking, was designed to solve.

Further Reading

For those wishing to explore this topic in greater detail, the following resources provide authoritative and in-depth information.

- The

ldandarman pages: The official documentation on your Linux system. Access them viaman ldandman ar. They are the definitive source for all command-line options. https://www.man7.org/linux/man-pages/man1/ld.1.html - Linkers and Loaders by John R. Levine: A comprehensive book covering the theory and practice of linking and loading on various systems.

- Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective by Randal E. Bryant and David R. O’Hallaron: Chapter 7, “Linking,” provides one of the best academic explanations of the entire linking process.

- Buildroot Manual: The official documentation for the Buildroot embedded Linux build system contains excellent sections on how it handles static and dynamic library configuration for a target system. https://buildroot.org/downloads/manual/manual.html

- Yocto Project Mega-Manual: Similar to the Buildroot manual, the Yocto Project’s documentation details its extensive mechanisms for managing package dependencies and library types.