Chapter 92: Error Reporting Strategies in Linux

Chapter Objectives

Upon completing this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the fundamental role of the

errnovariable in the Linux C library for signaling system-level errors. - Implement basic error reporting using the

perror()function to quickly diagnose issues during development. - Utilize the

strerror()and thread-safestrerror_r()functions to create flexible and robust error messages. - Design and implement a custom, context-aware logging framework suitable for embedded applications.

- Diagnose and troubleshoot common pitfalls associated with error handling in C programs.

- Apply these error reporting techniques to build more reliable and maintainable embedded Linux applications on the Raspberry Pi 5.

Introduction

In the world of embedded systems, software failure is not merely an inconvenience; it can lead to unresponsive devices, data corruption, or even unsafe operating conditions. A headless embedded device, such as a sensor node deployed in a remote field or a controller mounted deep within an industrial machine, offers no screen or console for a user to see what has gone wrong. Therefore, the ability to programmatically capture and report errors is a cornerstone of reliable embedded software development. Without robust error handling, debugging becomes a frustrating exercise in guesswork, and system failures in the field become nearly impossible to diagnose.

This chapter delves into the essential error reporting mechanisms available in the standard C library on a Linux system. We will begin by exploring the foundational concept of errno, the global variable that the Linux kernel and C library use to communicate the specific nature of a failure. From there, we will examine the simplest tool for decoding errno, the perror() function, which provides a quick and direct way to print error messages. We will then advance to the more versatile strerror() and its thread-safe counterpart, strerror_r(), which allow developers to integrate system error descriptions into custom logging formats.

The culmination of this chapter will be the design of a practical, custom logging framework. This is where theory meets practice in embedded development. You will learn to create structured, informative error messages that include not only the system-level problem but also vital application context, such as the source file, function name, and line number where the error occurred. By the end of this chapter, you will have moved beyond simple printf debugging and will be equipped to build resilient embedded applications that can clearly report their status, simplifying development, testing, and long-term maintenance.

Technical Background

The Nature of Errors in System Programming

In an ideal world, every function call would succeed. In reality, programs interact with a complex and unpredictable environment. Files may not exist, network connections can drop, memory can be exhausted, and hardware devices may not have the required permissions. In the C programming language, particularly within the context of Linux system programming, errors are not handled through exceptions as they are in languages like C++ or Python. Instead, a convention-based approach is used: system calls and many standard library functions signal failure through their return values.

A common pattern is for a function to return a special value, often NULL for functions that return pointers or -1 for functions that return integers, to indicate that an error has occurred. For example, the fopen() function returns a FILE pointer on success and NULL on failure. Similarly, the write() system call returns the number of bytes written on success and -1 on failure.

However, a return value of -1 only tells us that an error happened, not why. Did fopen() fail because the file does not exist, or because the program lacks the necessary permissions to read it? To provide this crucial context, the system uses a special variable named errno.

Understanding errno

When a system call or a C library function fails, it not only returns a value like -1 but also sets an integer variable called errno to a positive value that corresponds to the specific error. The C standard defines errno as a modifiable lvalue of type int. The header file <errno.h> provides the declaration for errno and defines symbolic constants for each error code, such as EACCES for “Permission denied” or ENOENT for “No such file or directory.”

It is a critical and often misunderstood point that errno is only meaningful immediately after a function call has indicated failure. A successful function call is not required to reset errno to zero. Therefore, you must never write code that checks the value of errno without first checking the function’s return value.

// Incorrect usage: errno might hold a stale value from a previous, unrelated error.

FILE *f = fopen("data.txt", "r");

if (errno == ENOENT) {

printf("File not found.\n"); // This might execute even if fopen() succeeded!

}

// Correct usage: First check the return value, then check errno.

FILE *f = fopen("data.txt", "r");

if (f == NULL) {

// Now it's safe to check errno.

if (errno == ENOENT) {

printf("Error: The file 'data.txt' does not exist.\n");

} else if (errno == EACCES) {

printf("Error: Permission denied to read 'data.txt'.\n");

} else {

// Handle other potential errors.

}

}

%%{ init: { 'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'fontFamily': 'Open Sans' } } }%%

graph LR

subgraph Correct Error Handling Logic

A["Start: Call a system function<br>e.g., fopen()"] --> B{Check return value};

B -- "Success (e.g., not NULL, not -1)" --> C[Proceed with normal logic];

B -- "Failure (e.g., NULL, -1)" --> D[Immediately save errno<br><i>int saved_errno = errno;</i>];

D --> E{Choose reporting strategy};

E -- "Simple/Quick Debug" --> F["Call perror(\Context message\)"];

E -- "Flexible/Logging" --> G["Use strerror_r() to get error string"];

G --> H[Format a custom log message<br>including the error string];

F --> I["Handle error gracefully<br>(e.g., cleanup, exit)"];

H --> I;

C --> J[End];

I --> J;

end

%% Styling

style A fill:#1e3a8a,stroke:#1e3a8a,stroke-width:2px,color:#ffffff

style J fill:#10b981,stroke:#10b981,stroke-width:2px,color:#ffffff

style B fill:#f59e0b,stroke:#f59e0b,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style E fill:#f59e0b,stroke:#f59e0b,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style C fill:#0d9488,stroke:#0d9488,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style D fill:#ef4444,stroke:#ef4444,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style F fill:#8b5cf6,stroke:#8b5cf6,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style G fill:#8b5cf6,stroke:#8b5cf6,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style H fill:#0d9488,stroke:#0d9488,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style I fill:#eab308,stroke:#eab308,stroke-width:1px,color:#1f2937

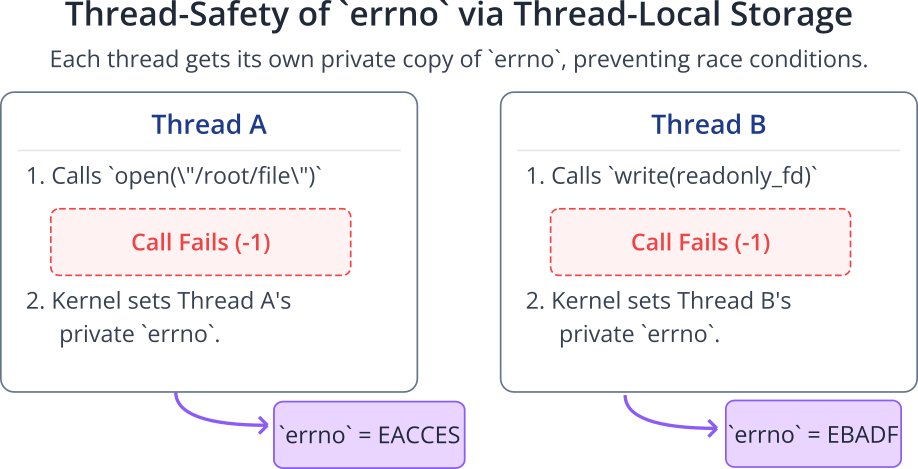

Historically, errno was a true global variable. This posed a significant problem for multi-threaded applications. If one thread’s system call failed and set errno, another thread could make a different system call that also failed, overwriting the first thread’s errno value before it could be read. To solve this, modern C libraries and compilers, including the GNU C Library (glibc) used in Linux, define errno in a way that makes it thread-local. On Linux, errno is typically a macro that expands to a function call returning a pointer to a thread-specific integer location. This ensures that each thread has its own private errno, preventing race conditions and making error handling in concurrent programs safe.

The perror() Function

While you can check errno against specific constants like ENOENT, this requires writing a large if-else or switch statement to handle all possible errors. For many simple cases, a more direct approach is sufficient. The perror() function, declared in <stdio.h>, provides a straightforward way to print an error message to the standard error stream (stderr).

The function signature is:

void perror(const char *s);perror() produces a message on stderr that consists of two parts: the string s that you provide, followed by a colon and a space, and then a human-readable message corresponding to the current value of errno. If the string s is NULL or an empty string, only the system error message is printed.

Consider a program that tries to open a non-existent file for reading:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <errno.h>

int main(void) {

FILE *f = fopen("non_existent_file.txt", "r");

if (f == NULL) {

// The return value indicates failure, so we can now use perror().

perror("Failed to open file");

return 1;

}

printf("File opened successfully.\n");

fclose(f);

return 0;

}

If you compile and run this program, the output will be:

Failed to open file: No such file or directory

This is incredibly useful for quick debugging. The custom prefix “Failed to open file” provides application-level context, while the system-generated part “No such file or directory” tells you exactly why the fopen() call failed. perror() is simple, effective, and ideal for command-line tools or during the early stages of development. However, its direct writing to stderr makes it inflexible for embedded systems where errors must be sent to a log file, a network socket, or a non-standard serial port.

The strerror() Function

For more control over error reporting, the C library provides the strerror() function, declared in <string.h>. This function takes an error number as an argument and returns a pointer to the corresponding human-readable error string.

The function signature is:

char *strerror(int errnum);Unlike perror(), strerror() does not print anything. It simply gives you the descriptive string, which you can then incorporate into any output mechanism you choose. This is a significant advantage in embedded systems.

Here is the previous example, rewritten to use strerror() to log the error to stdout instead of stderr:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <errno.h>

int main(void) {

FILE *f = fopen("non_existent_file.txt", "r");

if (f == NULL) {

// The return value indicates failure.

// We capture errno immediately in a local variable.

int saved_errno = errno;

printf("LOG: Failed to open file. Reason: %s\n", strerror(saved_errno));

return 1;

}

printf("File opened successfully.\n");

fclose(f);

return 0;

}

Tip: It is good practice to save the value of

errnoto a local variable immediately after a failed function call. Subsequent function calls, evenprintf(), could potentially modifyerrno, leading to incorrect error reporting.

The output of this program would be:

LOG: Failed to open file. Reason: No such file or directory

This approach is far more flexible. The error message can be formatted, combined with other data, and directed to any output stream. However, strerror() has a hidden danger in multi-threaded programs. The string it returns often points to a static, internal buffer. If two threads call strerror() at nearly the same time, one thread’s output might overwrite the other’s before it can be used, resulting in a race condition and garbled error messages. This led to the development of a thread-safe alternative: strerror_r().

Thread-Safe Error Reporting with strerror_r()

The strerror_r() function is designed to be a thread-safe replacement for strerror(). It resolves the static buffer problem by having the caller provide the buffer where the error string will be stored. Unfortunately, its history has led to two different, incompatible versions, which can be a source of confusion.

- The XSI-compliant (POSIX) version: This is the standardized version and is preferred for portable code.int strerror_r(int errnum, char *buf, size_t buflen);This function populates the user-provided buf of size buflen with the error string. It returns 0 on success. On failure, it returns an error number (e.g., EINVAL if errnum is invalid, or ERANGE if buflen is too small), and the contents of buf are implementation-defined.

- The GNU-specific version: This is the default on Linux systems unless certain macros are defined to request POSIX compliance.char *strerror_r(int errnum, char *buf, size_t buflen);This version also populates the user-provided buf. However, it returns a pointer to the error string. This returned pointer might be a pointer to buf itself, or it might be a pointer to a different, static string if the error message is short and already available. This behavior, while potentially more efficient, is non-standard and less predictable.

To ensure you are using the more portable XSI-compliant version, you can define feature test macros like _POSIX_C_SOURCE >= 200112L before including any headers.

Using the XSI-compliant strerror_r() looks like this:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <errno.h>

#define MSG_BUF_SIZE 256

int main(void) {

FILE *f = fopen("non_existent_file.txt", "r");

if (f == NULL) {

int saved_errno = errno;

char error_msg[MSG_BUF_SIZE];

// Use the XSI-compliant strerror_r

if (strerror_r(saved_errno, error_msg, MSG_BUF_SIZE) == 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Failed to open file. Reason: %s\n", error_msg);

} else {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Failed to open file. Unknown error occurred.\n");

}

return 1;

}

// ...

return 0;

}

This approach is robust, thread-safe, and the recommended practice for professional embedded software.

Custom Error Messaging Strategies

While perror() and strerror_r() are excellent for reporting system-level errors, they lack application-specific context. An error message like “Permission denied” is helpful, but “Failed to initialize I2C bus: Permission denied” is far better. A truly robust logging system for an embedded device should provide as much context as possible to aid in remote debugging.

A powerful strategy involves creating a custom logging function or set of macros. This framework can automatically capture not only the system error but also information about where in the code the error occurred. The C preprocessor provides several useful macros for this purpose:

__FILE__: Expands to the name of the current source file as a string literal.__LINE__: Expands to the current line number in the source file as an integer constant.__func__(or__FUNCTION__): Expands to the name of the current function as a string literal.

By combining these macros with strerror_r(), we can build a highly informative logging system. A good logging framework should also support different log levels, such as DEBUG, INFO, WARNING, ERROR, and CRITICAL. This allows a developer to control the verbosity of the log output. During development, you might enable DEBUG-level logging to see everything. In a production deployment, you might only log WARNING-level messages and above to save storage space and reduce noise.

A custom error logging function might look like this:

// A prototype for a custom logger

void app_log(LogLevel level, const char *file, int line, const char *func, const char *fmt, ...);

This function could be designed to format a message containing the log level, timestamp, file, line, and function name, along with a user-provided message. When a system error is involved, it can be passed into the formatted string.

For example, a call might look like this:

app_log(ERROR, __FILE__, __LINE__, __func__, "Failed to open '%s': %s", filename, strerror(errno));This approach centralizes logging logic, making it easy to change the output destination (e.g., from console to a file or network socket) by modifying only the app_log function. It provides the rich, contextual information that is invaluable when a bug appears on a device that is miles away. This is the level of professionalism expected in commercial embedded Linux development.

Practical Examples

In this section, we will apply the concepts discussed to the Raspberry Pi 5. The examples will be compiled directly on the Pi, but in a professional setting, you would typically use a cross-compilation toolchain on a more powerful host machine.

Build and Configuration Steps

For these examples, you will need a Raspberry Pi 5 running a standard Raspberry Pi OS (Debian-based) distribution. You can write, compile, and run the code directly on the Pi using a terminal.

1. Access your Raspberry Pi: Connect via SSH or use a monitor and keyboard.

2. Install Build Tools: Ensure you have the C compiler and related tools.

sudo apt update

sudo apt install build-essential2. Create a Workspace:

mkdir ~/error_handling_examples

cd ~/error_handling_examplesCompiling a C file: For each example, you will save the code to a .c file (e.g., example1.c) and compile it using gcc.

gcc -Wall -o example1 example1.c-Wall flag enables all compiler warnings, which is a highly recommended practice.

Example 1: Basic Error Reporting with perror()

This example demonstrates the most direct way to report an error. We will attempt to create a directory in a location where we don’t have permission (/) and use perror() to see the result.

Code (perror_example.c):

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <errno.h>

int main(void) {

// Attempt to create a directory at the root.

// We use 0755 for permissions (rwxr-xr-x).

int result = mkdir("/new_directory_test", 0755);

if (result == -1) {

// The mkdir call failed. Check errno.

perror("Error creating directory");

// Explain the error for clarity in this example.

if (errno == EACCES) {

printf("Diagnosis: The program lacks permission to create a directory there.\n");

} else if (errno == EROFS) {

printf("Diagnosis: The root filesystem is read-only.\n");

}

return 1; // Indicate failure to the shell

}

printf("Directory '/new_directory_test' created successfully.\n");

// In a real program, you'd likely want to clean up.

// rmdir("/new_directory_test");

return 0; // Indicate success

}

Build and Run:

gcc -Wall -o perror_example perror_example.c

./perror_example

Expected Output:

Error creating directory: Permission denied

Diagnosis: The program lacks permission to create a directory there.

This output clearly shows perror() in action. It prints our custom message (“Error creating directory”) followed by the system’s explanation for the EACCES error (“Permission denied”).

Example 2: Flexible Error Handling with strerror()

Here, we will redirect our error message to a log file instead of stderr. This simulates a common requirement for embedded devices that log their activity for later analysis.

Code (strerror_example.c):

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <time.h>

// A simple function to log messages to a file.

void log_to_file(const char *message) {

FILE *logfile = fopen("app.log", "a"); // "a" for append

if (logfile == NULL) {

perror("Critical error: could not open log file");

return;

}

// Get current time for the log entry

time_t now = time(NULL);

char time_str[30];

strftime(time_str, sizeof(time_str), "%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S", localtime(&now));

fprintf(logfile, "[%s] %s\n", time_str, message);

fclose(logfile);

}

int main(void) {

const char *filename = "/etc/shadow"; // A file we can't read

log_to_file("INFO: Application starting. Attempting to read sensitive file.");

FILE *f = fopen(filename, "r");

if (f == NULL) {

// Failure! Save errno immediately.

int saved_errno = errno;

char error_buffer[512];

// Format a detailed error message using strerror()

snprintf(error_buffer, sizeof(error_buffer),

"ERROR: Failed to open file '%s'. Reason: %s",

filename, strerror(saved_errno));

log_to_file(error_buffer);

fprintf(stderr, "An error occurred. Check app.log for details.\n");

return 1;

}

log_to_file("SUCCESS: File opened. This should not happen!");

fclose(f);

return 0;

}

Build and Run:

gcc -Wall -o strerror_example strerror_example.c

./strerror_example

Expected Output (to console):

An error occurred. Check app.log for details.

File Content (app.log):

After running the program, check the contents of the log file.

cat app.log

You should see something like this (timestamp will vary):

[2025-08-01 12:54:00] INFO: Application starting. Attempting to read sensitive file.

[2025-08-01 12:54:00] ERROR: Failed to open file '/etc/shadow'. Reason: Permission denied

This example shows the power of strerror(). We have full control over the error message format and destination, allowing us to create persistent, timestamped logs.

Example 3: Thread-Safe Errors with strerror_r()

This example highlights why strerror_r() is essential in multi-threaded code. We will spawn two threads that each trigger a different error. Using the thread-safe function ensures each thread reports its error correctly.

Code (threadsafe_example.c):

// Define this to get the XSI-compliant version of strerror_r

#define _POSIX_C_SOURCE 200112L

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#define ERROR_BUF_SIZE 256

// Thread function

void* worker_thread(void *arg) {

int task_id = *(int*)arg;

char error_msg[ERROR_BUF_SIZE];

printf("Thread %d: Starting.\n", task_id);

if (task_id == 1) {

// Task 1: Try to open a file that is actually a directory.

FILE *f = fopen("/", "r");

if (f == NULL) {

int saved_errno = errno;

if (strerror_r(saved_errno, error_msg, sizeof(error_msg)) == 0) {

printf("Thread %d ERROR: Failed to open '/'. Reason: %s\n", task_id, error_msg);

}

} else {

fclose(f);

}

} else if (task_id == 2) {

// Task 2: Try to write to a read-only file descriptor (stdin).

if (write(STDIN_FILENO, "test", 4) == -1) {

int saved_errno = errno;

if (strerror_r(saved_errno, error_msg, sizeof(error_msg)) == 0) {

printf("Thread %d ERROR: Failed to write to stdin. Reason: %s\n", task_id, error_msg);

}

}

}

printf("Thread %d: Finished.\n", task_id);

return NULL;

}

int main(void) {

pthread_t t1, t2;

int id1 = 1, id2 = 2;

printf("Main: Creating threads.\n");

// Create two threads

pthread_create(&t1, NULL, worker_thread, &id1);

pthread_create(&t2, NULL, worker_thread, &id2);

// Wait for them to complete

pthread_join(t1, NULL);

pthread_join(t2, NULL);

printf("Main: Threads finished. Exiting.\n");

return 0;

}

Build and Run (link with pthread library):

gcc -Wall -o threadsafe_example threadsafe_example.c -lpthread

./threadsafe_example

Expected Output (order of lines may vary):

Main: Creating threads.

Thread 1: Starting.

Thread 2: Starting.

Thread 1 ERROR: Failed to open '/'. Reason: Is a directory

Thread 1: Finished.

Thread 2 ERROR: Failed to write to stdin. Reason: Bad file descriptor

Thread 2: Finished.

Main: Threads finished. Exiting.

Each thread correctly reports its distinct error (“Is a directory” vs. “Bad file descriptor”). If we had used strerror(), there would be a risk of one thread’s error message overwriting the other’s, leading to incorrect logs.

Example 4: A Custom Logging Framework

This is the most practical and advanced example. We create a small, reusable logging library that provides different log levels and automatically includes file, line, and function context.

%%{ init: { 'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'fontFamily': 'Open Sans' } } }%%

graph TD

subgraph "Application Code (main_app.c)"

A("main()") --> B("perform_risky_operation()");

A --> C{"LOG_MSG(INFO, ...)"}

B --> D{"LOG_SYS_ERROR(...)"}

end

subgraph "Logging Framework"

direction LR

subgraph "logger.h (Public API)"

direction TB

Macro1(LOG_MSG Macro<br><i>Captures __FILE__, __LINE__, __func__</i>)

Macro2(LOG_SYS_ERROR Macro<br><i>Calls strerror_r</i>)

end

subgraph "logger.c (Implementation)"

direction TB

CoreFunc("logger_log()")

InitFunc("logger_init()")

CleanupFunc("logger_cleanup()")

end

Macro1 --> CoreFunc;

Macro2 --> Macro1;

C --> Macro1;

D --> Macro2;

A -- Calls --> InitFunc;

A -- Calls --> CleanupFunc;

CoreFunc -- "Formats message with<br>timestamp, level, context" --> CheckLevel{Is log level sufficient?};

CheckLevel -- Yes --> Write;

CheckLevel -- No --> Drop;

Write["Write to Output<br><i>(File or stderr)</i>"];

Drop[Discard Message];

end

subgraph "Output"

OutputDest(Log File<br><i>e.g., system.log</i>)

end

Write --> OutputDest

%% Styling

style A fill:#1e3a8a,stroke:#1e3a8a,stroke-width:2px,color:#ffffff

style B fill:#1e3a8a,stroke:#1e3a8a,stroke-width:2px,color:#ffffff

style C fill:#0d9488,stroke:#0d9488,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style D fill:#ef4444,stroke:#ef4444,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style CoreFunc fill:#8b5cf6,stroke:#8b5cf6,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style InitFunc fill:#0d9488,stroke:#0d9488,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style CleanupFunc fill:#0d9488,stroke:#0d9488,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style CheckLevel fill:#f59e0b,stroke:#f59e0b,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style Write fill:#10b981,stroke:#10b981,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style Drop fill:#eab308,stroke:#eab308,stroke-width:1px,color:#1f2937

style Macro1 fill:#4f46e5,stroke:#4338ca,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style Macro2 fill:#4f46e5,stroke:#4338ca,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style OutputDest fill:#374151,stroke:#1f2937,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

File Structure:

error_handling_examples/

├── logger.h

├── logger.c

└── main_app.c

logger.h:

#ifndef LOGGER_H

#define LOGGER_H

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <errno.h>

typedef enum {

LOG_DEBUG,

LOG_INFO,

LOG_WARN,

LOG_ERROR,

LOG_CRITICAL

} LogLevel;

// Function to set the output file and minimum log level

void logger_init(LogLevel level, const char* filename);

void logger_cleanup(void);

// The core logging function

void logger_log(LogLevel level, const char* file, int line, const char* func, const char* fmt, ...);

// Macros to make logging easier and automatic

#define LOG_MSG(level, ...) logger_log(level, __FILE__, __LINE__, __func__, __VA_ARGS__)

// A special macro for logging system errors from errno

#define LOG_SYS_ERROR(message) \

do { \

char err_buf[256]; \

strerror_r(errno, err_buf, sizeof(err_buf)); \

LOG_MSG(LOG_ERROR, "%s: %s", message, err_buf); \

} while (0)

#endif // LOGGER_H

logger.c:

#include "logger.h"

#include <stdarg.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

static LogLevel current_level = LOG_INFO;

static FILE* output_stream = NULL;

void logger_init(LogLevel level, const char* filename) {

current_level = level;

if (filename) {

output_stream = fopen(filename, "a");

if (!output_stream) {

perror("Failed to open log file");

output_stream = stderr; // Fallback to stderr

}

} else {

output_stream = stderr;

}

}

void logger_cleanup(void) {

if (output_stream && output_stream != stderr) {

fclose(output_stream);

}

}

void logger_log(LogLevel level, const char* file, int line, const char* func, const char* fmt, ...) {

if (level < current_level) {

return; // Don't log messages below the current level

}

// Get time

time_t now = time(NULL);

char time_str[30];

strftime(time_str, sizeof(time_str), "%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S", localtime(&now));

// Log level to string

const char* level_str[] = {"DEBUG", "INFO", "WARN", "ERROR", "CRITICAL"};

// Print the log prefix

fprintf(output_stream, "[%s] [%s] [%s:%d %s()] ", time_str, level_str[level], file, line, func);

// Print the user message

va_list args;

va_start(args, fmt);

vfprintf(output_stream, fmt, args);

va_end(args);

fprintf(output_stream, "\n");

fflush(output_stream); // Ensure message is written immediately

}

main_app.c:

#include "logger.h"

#include <unistd.h>

void perform_risky_operation(void) {

LOG_MSG(LOG_INFO, "Attempting to change directory to a protected area.");

if (chdir("/root") == -1) {

// Use our special macro to log the system error

LOG_SYS_ERROR("Failed to chdir to /root");

} else {

LOG_MSG(LOG_INFO, "Successfully changed to /root. This should not happen!");

}

}

int main(void) {

// Initialize logger to log INFO and above to "system.log"

logger_init(LOG_INFO, "system.log");

LOG_MSG(LOG_INFO, "Application starting up.");

LOG_MSG(LOG_DEBUG, "This is a debug message and should NOT appear in the log.");

perform_risky_operation();

LOG_MSG(LOG_WARN, "A non-critical issue was detected, but we are continuing.");

LOG_MSG(LOG_CRITICAL, "Shutting down due to a simulated critical event.");

logger_cleanup();

return 0;

}

Build and Run:

# Compile the logger and the main app, then link them

gcc -Wall -c -o logger.o logger.c

gcc -Wall -c -o main_app.o main_app.c

gcc -o main_app logger.o main_app.o

# Run the application

./main_app

File Content (system.log):

cat system.log

The output will be highly detailed and contextual:

[2025-08-01 12:54:05] [INFO] [main_app.c:16 main()] Application starting up.

[2025-08-01 12:54:05] [INFO] [main_app.c:6 perform_risky_operation()] Attempting to change directory to a protected area.

[2025-08-01 12:54:05] [ERROR] [main_app.c:9 perform_risky_operation()] Failed to chdir to /root: Permission denied

[2025-08-01 12:54:05] [WARN] [main_app.c:21 main()] A non-critical issue was detected, but we are continuing.

[2025-08-01 12:54:05] [CRITICAL] [main_app.c:22 main()] Shutting down due to a simulated critical event.

This custom framework provides everything needed for professional-grade logging in an embedded system. The messages are timestamped, categorized by severity, and pinpoint the exact location in the source code where the event occurred.

Common Mistakes & Troubleshooting

Even with the right tools, error handling is fraught with potential pitfalls. Awareness of these common mistakes can save hours of debugging.

Exercises

- Exploring File System Errors:

- Objective: Understand the different error codes related to file operations.

- Task: Modify the

perror_example.cprogram. Instead ofmkdir(), usefopen(). In a loop, prompt the user to enter a filename. Try to open the file and useperror()to report the result. - Verification: Test with the following inputs and observe the output from

perror():- A file that does not exist (e.g.,

nosuchfile.txt). - A file you don’t have permission to read (e.g.,

/etc/sudoers). - A path that is a directory (e.g.,

/home). - A path where a component is not a directory (e.g., create a file named

not_a_dirand then try to opennot_a_dir/somefile.txt).

- A file that does not exist (e.g.,

- Extending the Custom Logger:

- Objective: Enhance the custom logging framework to make it more flexible.

- Task: Modify the

logger.clibrary from Example 4. Add a functionlogger_set_stream(FILE *stream)that allows the user to redirect log output to any open file stream (likestdout,stderr, or a file opened in the main application). - Verification: In

main_app.c, initialize the logger to write tosystem.log. Then, calllogger_set_stream(stdout)and log a few more messages. Confirm that the initial logs went to the file and the subsequent logs went to the console.

- Generating a System Error List:

- Objective: Become familiar with the range of system errors on your platform.

- Task: Write a small C program that iterates from

errnum = 1up to255. For each number, use the thread-safestrerror_r()to get the corresponding error message and print both the number and the message to the console, like"Error 1: EPERM - Operation not permitted". - Guidance: You can find the symbolic names (like

EPERM) in<errno.h>. While you can’t easily iterate over the names themselves, printing the number and the string is sufficient. This gives you a quick reference for all possible system errors.

- Refactoring with the Logging Framework:

- Objective: Apply the custom logging framework to an existing piece of code.

- Task: Find a simple C program you have written previously (e.g., a basic socket client/server, a file copy utility). Remove all

printfandperrorcalls used for debugging or error reporting. Integrate thelogger.hlibrary and replace the old error reporting with calls toLOG_MSG,LOG_WARN, andLOG_SYS_ERROR. - Verification: Run the refactored program and trigger both success and failure conditions. Check the log output to ensure it is more structured and informative than the original

printfstatements.

Summary

- Errors are Signaled by Return Values: In C, functions typically return

-1orNULLto indicate failure. This is the primary signal to check for an error. errnoProvides the Reason: After a failure is signaled, theerrnovariable contains an integer code that specifies the why behind the error. It is thread-safe on modern Linux systems.perror()is for Simple, Direct Reporting: It prints a user-defined string and the system error message for the currenterrnodirectly tostderr. It is quick but inflexible.strerror()andstrerror_r()Offer Flexibility: These functions return the error string, allowing the programmer to format it and direct it to any destination (file, network, etc.).strerror_r()is the required thread-safe version for robust applications.- Custom Logging Frameworks are Essential: For production embedded systems, a custom logger that captures application context (

__FILE__,__LINE__,__func__), supports log levels, and usesstrerror_r()is the professional standard. - Diligent Checking is Non-Negotiable: Always check function return values, save

errnoimmediately, and handle potential errors gracefully. Robustness is built from disciplined coding practices.

Further Reading

- The GNU C Library (glibc) Manual – Error Reporting: The official documentation for

errno,perror, andstrerror. An authoritative source. - Linux man-pages –

errno(3): The definitive Linux manual page forerrno, listing the standard error codes. - Linux man-pages –

strerror(3): The manual page forstrerror,strerror_r, and related functions, detailing the differences between the XSI and GNU versions. - POSIX Standard for

strerror: The official standard from the Open Group, defining the portable behavior ofstrerror_r. - “Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment” by W. Richard Stevens and Stephen A. Rago: A classic and highly respected text covering these topics in great detail. Chapter 1 provides an excellent overview of fundamental concepts including error handling.

- “The Linux Programming Interface” by Michael Kerrisk: An exhaustive guide to the Linux kernel and glibc APIs. The early chapters on fundamental concepts and file I/O provide deep insights into error handling patterns.

- Raspberry Pi Documentation: Official hardware and software documentation for the Raspberry Pi platform.