Chapter 86: Understanding Libraries: Purpose and Benefits

Chapter Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the fundamental differences between static and shared libraries and their respective trade-offs in embedded systems.

- Implement and compile your own static libraries (

.afiles) and link them into an application. - Implement, compile, and deploy shared libraries (

.sofiles) on a target system like the Raspberry Pi 5. - Configure the dynamic linker and manage library dependencies on an embedded Linux system.

- Debug common issues related to library versioning, symbol conflicts, and path resolution.

- Analyze an executable to determine its dependencies and understand the linking process.

Introduction

In the world of embedded Linux development, efficiency and reliability are paramount. As systems grow in complexity, from industrial controllers to sophisticated consumer electronics, the need for well-organized, reusable, and maintainable code becomes critical. This is where the concept of libraries becomes not just a convenience, but a cornerstone of professional software engineering. Libraries are pre-compiled collections of code—functions, data, and classes—that can be shared and reused across multiple applications. Without them, every project would require reinventing the wheel for common tasks like string manipulation, mathematical calculations, or hardware interfacing, leading to bloated, error-prone, and unmanageable codebases.

This chapter delves into the purpose and benefits of using libraries in the context of embedded Linux systems, using the Raspberry Pi 5 as our practical development platform. We will explore the two primary types of libraries: static libraries and shared libraries (also known as dynamic libraries). You will learn how each type is created, how they are linked into your applications, and the profound impact this choice has on memory usage, application size, and system updates—all critical considerations in resource-constrained embedded environments. By mastering the use of libraries, you will not only write more modular and efficient code but also gain the ability to leverage the vast ecosystem of open-source software that powers the Linux world. This chapter will equip you with the foundational knowledge to structure your embedded applications professionally, manage dependencies effectively, and build robust systems that are easier to debug, maintain, and scale.

Technical Background

The concept of a software library is as old as modern programming itself, born from the fundamental desire to avoid redundant work. In the early days of computing, programmers would physically share decks of punch cards containing common routines. As operating systems and toolchains matured, this ad-hoc sharing evolved into a formalized system of pre-compiled object files that could be programmatically linked into a new application. This evolution was driven by the core principles of modularity, reusability, and abstraction. In embedded Linux, these principles are not just academic; they have direct consequences on system performance, storage footprint, and maintainability.

The Anatomy of a Library: From Source to Object Code

Before a library can be used, it must first be created from source code. The process begins with a standard compiler, such as the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), which is the de facto standard for Linux development. The compiler takes human-readable source files (e.g., .c or .cpp files) and translates them into object code. An object file (typically with a .o extension) contains machine code—the raw binary instructions that a CPU can execute—but it is not yet a complete program. It also contains metadata, most importantly a symbol table.

A symbol is essentially a name that refers to a piece of data or a function within the object file. For example, if you write a C function named int calculate_pi(void), the compiled object file will contain a symbol named calculate_pi that points to the starting address of that function’s machine code. The object file also lists any undefined symbols—symbols that are used by the code (e.g., a call to printf) but are not defined within that same file. The task of resolving these undefined symbols by finding their definitions in other object files or libraries is handled by a program called the linker. It is at this linking stage that the choice between static and shared libraries becomes critical.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'lineColor': '#64748b', 'primaryTextColor': '#1f2937', 'fontSize': '15px'}}}%%

graph TD

subgraph Compilation Process

direction LR

A[<b>C Source File</b><br><i>e.g., add.c</i>] -->|gcc -c add.c| B{GCC Compiler};

B --> C((<b>Object File</b><br><i>add.o</i>));

end

subgraph "Object File Contents"

direction TB

C --> D[Machine Code<br><i>Binary CPU Instructions</i>];

C --> E{Symbol Table};

end

subgraph "Symbol Table Details"

direction TB

E --> F[<b>Defined Symbols</b><br><i>e.g., 'add' function</i>];

E --> G[<b>Undefined Symbols</b><br><i>e.g., call to 'printf'</i>];

end

style A fill:#1e3a8a,stroke:#1e3a8a,stroke-width:2px,color:#ffffff

style B fill:#0d9488,stroke:#0d9488,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style C fill:#8b5cf6,stroke:#8b5cf6,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style D fill:#374151,stroke:#374151,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style E fill:#f59e0b,stroke:#f59e0b,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style F fill:#10b981,stroke:#10b981,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffff

style G fill:#ef4444,stroke:#ef4444,stroke-width:1px,color:#ffffffStatic Libraries: The Self-Contained Approach

A static library, which by convention has a .a (for “archive”) extension on Linux, is the simplest form of a library. It is, in essence, an archive of object files bundled together into a single file. The tool used to create a static library is an archiver, typically ar. When you link your application against a static library, the linker behaves as if it were given all the individual object files from the archive. It scans the library to find the object files that contain the definitions for any undefined symbols in your main program.

Once the linker finds a required object file within the static library, it copies the entire contents of that object file—all its functions and data—directly into your final executable file. This process is known as static linking. The result is a completely self-contained executable. It has no external dependencies on library files to run; all the necessary code is embedded within it.

This self-contained nature is the primary advantage of static linking in certain embedded contexts. If you are deploying a single, critical application on a device, static linking guarantees that the application will run without needing to worry about whether the correct library versions are present on the target system. This simplifies deployment and can enhance reliability, as there’s no risk of a system update breaking your application by changing or removing a required shared library.

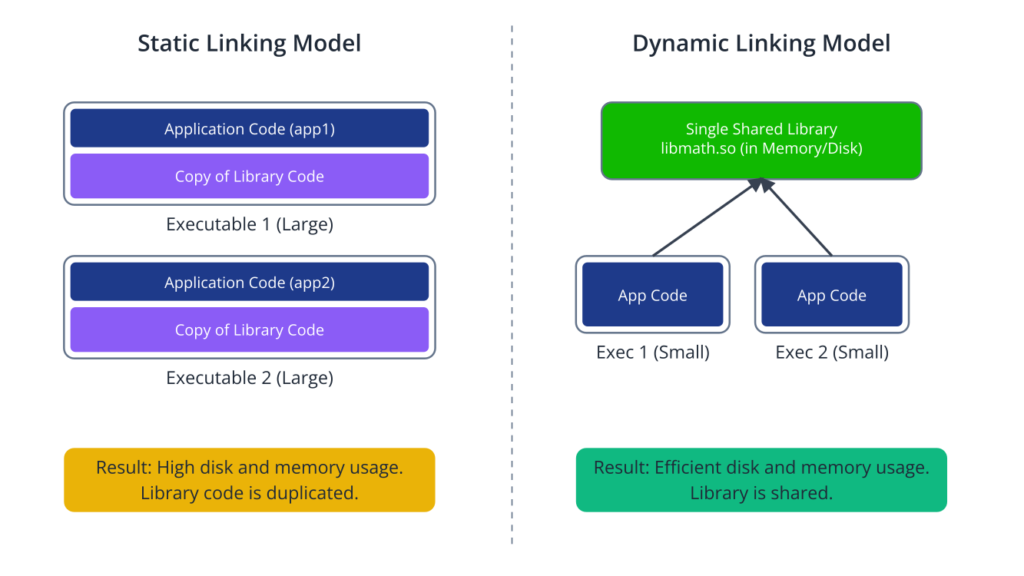

However, this approach has significant downsides. The most obvious is the increase in file size. If you have ten different applications on your system and they all statically link the same large library, ten copies of that library’s code will exist on your storage device, consuming a considerable amount of space. The problem is even more acute in memory (RAM). When those ten applications are running, ten separate copies of the library’s code are loaded into memory, which is highly inefficient and often untenable on memory-constrained embedded devices. Furthermore, updating a bug in a statically linked library is a major undertaking. You must recompile and redeploy every single application that uses it, rather than simply replacing one shared library file.

Shared Libraries: The Dynamic and Efficient Model

The inefficiencies of static linking led to the development of shared libraries, also known as dynamic libraries. On Linux, these files typically have a .so (for “shared object”) extension. Unlike a static library, a shared library is not copied into your executable at link time. Instead, the linker takes a different approach. When you link against a shared library, the linker notes the dependency in a special section of the executable. It records the names of the shared libraries the application needs (e.g., libc.so.6 or libmath.so.1) and the symbols it requires from them. The final executable is therefore much smaller, as it contains only its own code, not the code of the libraries it uses.

The real magic happens at runtime. When you execute the program, the operating system’s program loader inspects the executable’s metadata. Seeing the list of required shared libraries, it invokes another crucial component: the dynamic linker/loader (on most Linux systems, this is ld.so or ld-linux.so). The dynamic linker has the job of finding the required .so files on the filesystem, loading them into memory, and then performing the final symbol resolution. This process, called dynamic linking, involves mapping the library’s code into the application’s virtual address space and patching the application’s code to call the functions in the library at their now-known memory addresses.

The advantages of this model are immense, especially for a full-featured embedded Linux system like the one on a Raspberry Pi 5.

- Space Efficiency: A library exists as only one file on the storage device, regardless of how many applications use it. This drastically reduces the overall size of the root filesystem.

- Memory Efficiency: The kernel is smart about managing shared library memory. When multiple applications use the same shared library, the read-only code segment (known as the

.textsection) of that library is loaded into RAM only once. The kernel then maps this same physical memory into the virtual address space of each application. This results in a massive saving of physical RAM. - Maintainability: To fix a bug or apply a security patch to a shared library, you only need to replace the single

.sofile on the system. Every application that uses it will automatically benefit from the update the next time it is launched, without needing to be recompiled.

This model is not without its own set of challenges, often referred to as “dependency hell.” If an application was compiled expecting a specific version of a library (e.g., libcamera.so.0.3), but the system only has libcamera.so.0.2, the dynamic linker will fail to find the required symbols, and the application will refuse to start. To manage this, Linux systems use a sophisticated versioning scheme. The filename of a shared library often contains a version number (the soname), and symbolic links are used to abstract the specific version from the linker’s request. For instance, the linker might look for libcamera.so, which could be a symlink to libcamera.so.0, which in turn might be a symlink to the actual file, libcamera.so.0.3.1. This allows multiple versions to coexist and provides a stable interface for developers.

The Linking and Loading Process in Detail

To truly grasp how libraries work, we must look closer at the roles of the static linker (ld) and the dynamic linker (ld.so).

When you compile and link a program (e.g., gcc main.c -o myapp -lmylib), GCC first compiles main.c into main.o. It then invokes the static linker, ld. The linker’s job is to create the final executable, myapp. It processes main.o and sees a list of undefined symbols. When it processes -lmylib, it looks for a file named libmylib.so (for shared linking, which is the default) or libmylib.a (if shared is not found or if -static is specified).

If linking against a shared library libmylib.so, ld checks that all the symbols your program needs are indeed present in libmylib.so. It does not copy the code. Instead, it creates a placeholder in the executable. This placeholder essentially says, “at runtime, I will need the function foo from the library libmylib.so.” It also embeds the name libmylib.so into the executable as a dependency.

When the user runs ./myapp, the kernel’s loader maps the executable into memory and passes control to the dynamic linker, ld.so. The dynamic linker reads the dependency list from the executable’s header. For each library, like libmylib.so, it searches a predefined set of paths (configured in /etc/ld.so.conf and environment variables like LD_LIBRARY_PATH) to find the actual file. Once found, it opens the library file, maps its code and data segments into memory, and then resolves the symbols. It finds the address of foo within the loaded library and updates the placeholder in the main application’s code to point to this real address. Only after all dependencies are loaded and all symbols are resolved does ld.so pass control to the main function of your application. This intricate dance happens almost instantaneously every time you launch a dynamically linked program.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'lineColor': '#64748b', 'primaryTextColor': '#1f2937', 'fontSize': '15px', 'sequenceMessageColor': '#1f2937', 'sequenceActorFill': '#1e3a8a', 'sequenceActorColor': '#ffffff'}}}%%

sequenceDiagram

actor User

participant Kernel as Kernel

participant ld_so as Dynamic Linker (ld.so)

participant App as Application Code

participant lib_so as Shared Library (.so)

User->>Kernel: Executes command: ./shared_app

activate Kernel

Kernel->>ld_so: Loads App, finds dependencies,<br>passes control to ld.so

deactivate Kernel

activate ld_so

ld_so->>lib_so: 1. Searches configured paths<br>(e.g., /usr/lib, LD_LIBRARY_PATH)

activate lib_so

lib_so-->>ld_so: 2. Finds and provides libmath.so

deactivate lib_so

ld_so->>App: 3. Maps library into memory &<br>resolves symbols (relocation)

activate App

ld_so->>App: 4. Transfers control to app's<br>'main' function

deactivate ld_so

App->>lib_so: App now calls library functions<br>directly (e.g., add())

lib_so-->>App: Returns result to App

App-->>User: Program runs and exits

deactivate App

Practical Examples

Theory provides the foundation, but true understanding comes from hands-on practice. In this section, we will walk through the complete process of creating, linking, and deploying both static and shared libraries on a Raspberry Pi 5. We will use the GCC toolchain, which is standard on Raspberry Pi OS.

For these examples, ensure you have a Raspberry Pi 5 running a recent version of Raspberry Pi OS (Debian Bookworm or newer) and are comfortable working in the terminal.

Example 1: Creating and Using a Static Library

Let’s create a simple static library for performing basic arithmetic operations. This library will contain functions for addition and subtraction.

Step 1: Create the Library Source Code

First, create a directory for our project and navigate into it.

mkdir static_math_lib_project

cd static_math_lib_project

Inside this directory, create two source files for our library functions.

add.c

// add.c

// This file contains the implementation of the add function.

/**

* @brief Adds two integers.

* * @param a The first integer.

* @param b The second integer.

* @return The sum of a and b.

*/

int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

subtract.c

// subtract.c

// This file contains the implementation of the subtract function.

/**

* @brief Subtracts the second integer from the first.

* * @param a The integer to be subtracted from.

* @param b The integer to subtract.

* @return The result of a - b.

*/

int subtract(int a, int b) {

return a - b;

}

We also need a header file that applications will include to see the function prototypes.

math_lib.h

// math_lib.h

// Public header file for our math library.

// It declares the functions that are available to client applications.

#ifndef MATH_LIB_H

#define MATH_LIB_H

// Function prototypes

int add(int a, int b);

int subtract(int a, int b);

#endif // MATH_LIB_H

Step 2: Compile the Library Source into Object Files

Now, we compile each .c file into its corresponding object file (.o) using GCC. The -c flag tells the compiler to stop after the compilation phase and not proceed to linking.

gcc -c add.c -o add.o

gcc -c subtract.c -o subtract.o

After running these commands, you will have add.o and subtract.o in your directory.

Step 3: Create the Static Library Archive

With the object files ready, we use the ar (archiver) utility to bundle them into a static library. The convention is to name the library file lib<name>.a. We will call our library math.

ar rcs libmath.a add.o subtract.o

r: Replace older object files in the library with new ones.c: Create the archive if it doesn’t already exist.s: Write an object-file index into the archive, which speeds up the linker.

You now have a static library file named libmath.a. You can inspect its contents with ar -t:

$ ar -t libmath.a

add.o

subtract.o

Step 4: Create and Compile the Main Application

Let’s write a simple program that uses our new library.

main.c

// main.c

// A simple application to demonstrate the use of our static math library.

#include <stdio.h>

#include "math_lib.h" // Include our library's header

int main() {

int x = 20;

int y = 10;

printf("Demonstrating static library usage:\n");

int sum = add(x, y);

printf("Sum of %d and %d is: %d\n", x, y, sum);

int diff = subtract(x, y);

printf("Difference of %d and %d is: %d\n", x, y, diff);

return 0;

}

Step 5: Link the Application with the Static Library

Now, we compile main.c and link it against libmath.a.

gcc main.c -L. -lmath -o static_app

Let’s break down this command:

gcc main.c: The source file for our application.-L.: This tells the linker to look for library files in the current directory (.).-lmath: This tells the linker to find and link the library namedmath. The linker automatically prependsliband appends.a(or.so), searching forlibmath.a.-o static_app: Specifies the name of the output executable.

Step 6: Run and Verify

You can now run the application.

./static_app

Expected Output:

Demonstrating static library usage:

Sum of 20 and 10 is: 30

Difference of 20 and 10 is: 20

The application runs successfully. To prove that the library code is indeed part of the executable, we can use the nm tool to inspect the symbol table of static_app. You will see that the symbols add and subtract are listed as defined within the application’s text (code) section.

Example 2: Creating and Using a Shared Library

Now let’s convert our math library into a shared library. The process is slightly different because the code must be position-independent.

Step 1: Compile Position-Independent Code (PIC)

When a shared library is loaded into memory, it can be placed at any virtual address. Therefore, its code cannot rely on absolute memory addresses. It must be compiled as Position-Independent Code (PIC). We achieve this with the -fPIC flag in GCC.

Create a new directory for this project.

mkdir shared_math_lib_project

cd shared_math_lib_project

# Copy the .c and .h files from the previous example

cp ../static_math_lib_project/*.c .

cp ../static_math_lib_project/*.h .

Now, compile the object files with the -fPIC flag.

gcc -c -fPIC add.c -o add.o

gcc -c -fPIC subtract.c -o subtract.o

Step 2: Create the Shared Library

Instead of using ar, we use GCC itself to create the shared library with the -shared flag.

gcc -shared -o libmath.so add.o subtract.o

This command links the object files together into a single shared object file named libmath.so.

Step 3: Create and Compile the Main Application

We can use the same main.c file as before. Let’s create it again in our current directory.

main.c

// main.c

// A simple application to demonstrate the use of our shared math library.

#include <stdio.h>

#include "math_lib.h"

int main() {

int x = 20;

int y = 10;

printf("Demonstrating shared library usage:\n");

int sum = add(x, y);

printf("Sum of %d and %d is: %d\n", x, y, sum);

int diff = subtract(x, y);

printf("Difference of %d and %d is: %d\n", x, y, diff);

return 0;

}

Compile and link the application. The command is identical to the one used for static linking. By default, GCC prefers shared libraries over static ones if both are available.

gcc main.c -L. -lmath -o shared_app

Step 4: Configure the Dynamic Linker and Run

If you try to run ./shared_app immediately, you will encounter an error:

$ ./shared_app

./shared_app: error while loading shared libraries: libmath.so: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

This happens because the dynamic linker (ld.so) does not know where to find libmath.so. It only searches in standard system directories (like /lib and /usr/lib) and paths specified in its cache. Our library is in the current directory, which is not a standard location.

We have a few ways to solve this for testing purposes. The most common is to use the LD_LIBRARY_PATH environment variable.

Tip:

LD_LIBRARY_PATHis great for development and testing, but it is generally considered bad practice to require it for a production application. The proper way is to install the library in a standard system path.

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=.

./shared_app

Now the application runs correctly.

Expected Output:

Demonstrating shared library usage:

Sum of 20 and 10 is: 30

Difference of 20 and 10 is: 20

To make the change permanent for a deployed system, you would copy the library to a standard location and update the linker cache.

# This requires superuser privileges

sudo cp libmath.so /usr/local/lib

sudo ldconfig

After this, the application will run without needing LD_LIBRARY_PATH.

To verify that shared_app is dynamically linked, use the ldd tool.

$ ldd ./shared_app

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x...)

libmath.so => ./libmath.so (0x...)

libc.so.6 (0x...)

/lib/ld-linux-aarch64.so.1 (0x...)

The output clearly shows that shared_app depends on libmath.so and the dynamic linker has found it in the current directory (./libmath.so).

Common Mistakes & Troubleshooting

Working with libraries, especially shared ones, can introduce a new class of problems that might be unfamiliar if you have only worked with single-file programs. Here are some common pitfalls and how to navigate them.

Exercises

- Extend the Math Library: Add new functions for multiplication and division to the shared math library project. Create

multiply.canddivide.c, ensuring you handle the case of division by zero gracefully (e.g., by returning a specific value or setting an error state). Update the header file, recompile the shared library, and modify the main application to test your new functions. - Library Dependency Investigation: Choose a common command-line utility on your Raspberry Pi, such as

lsorgrep. Use thelddcommand to find out which shared libraries it depends on. Pick one of the libraries listed (e.g.,libc.so.6) and use thereadelf -s /path/to/library.so | grep FUNCcommand to list some of the functions it provides. This exercise will give you an appreciation for how fundamental libraries are to the entire operating system. - Dynamic Loading at Runtime: C provides a special API for loading shared libraries programmatically at runtime. This is useful for creating plug-in architectures. Research the

dlopen(),dlsym(),dlclose(), anddlerror()functions. Modify themain.capplication to loadlibmath.sousingdlopen()instead of linking it at compile time. Usedlsym()to get pointers to theaddandsubtractfunctions, and then call them through those function pointers. Remember to link your application with the-ldlflag to include the dynamic loading library.

Summary

- Libraries are fundamental to modern software development, promoting code reusability, modularity, and maintainability.

- Static Libraries (

.a) are archives of object code. The linker copies the required code directly into the final executable, creating a larger, self-contained application with no runtime library dependencies. - Shared Libraries (

.so) are linked at runtime. The executable is smaller and only contains references to the libraries it needs. This saves significant storage space and RAM, as the library is loaded into memory only once and shared by all applications. - Position-Independent Code (PIC) is a requirement for shared library code, allowing it to be loaded at any memory address. It is enabled with the

-fPICcompiler flag. - The static linker (

ld) resolves symbols at compile time, while the dynamic linker/loader (ld.so) resolves symbols and loads libraries at runtime. - Tools like

ar,nm,ldd, andreadelfare essential for creating, inspecting, and debugging libraries and executables. - Properly managing library paths and versions is critical for ensuring application reliability in an embedded Linux environment.

Further Reading

- Linux man-pages: The manual pages for

ld(1),ld.so(8),ar(1),nm(1), andldd(1)are the authoritative sources for these tools. Access them viaman ldon your system. - How to Write Shared Libraries by Ulrich Drepper: An in-depth paper covering the technical details of creating shared libraries on Linux. (https://www.akkadia.org/drepper/dsohowto.pdf)

- The ELF Object File Format: The specification for the Executable and Linkable Format used by Linux. (https://refspecs.linuxfoundation.org/elf/elf.pdf)

- Buildroot – Making Embedded Linux Easy: Official documentation for the Buildroot tool, which heavily relies on managing library dependencies for building embedded systems. (https://buildroot.org/docs.html)

- Yocto Project Manual: The main documentation for the Yocto Project, another professional tool for building custom Linux distributions, where library management is a core concept. (https://docs.yoctoproject.org/mega-manual/latest/index.html)

- Raspberry Pi Documentation: Official hardware and software documentation for the Raspberry Pi platform. (https://www.raspberrypi.com/documentation/)